William K. Vanderbilt Jr.‘s Alva Base on Fisher Island in Florida

Following his marriage to Rosamund Warburton in 1927, William K. Vanderbilt, Jr. traded one of his yachts to Carl Fisher in exchange for seven acres on Fisher Island near Miami Beach.

The development of his winter home Alva Base was described in this 2013 article in the Miami Herald.

Enjoy,

Howard Kroplick

Miami Herald

April 27, 2013

BY ANDRES VIGLUCCI

Historic Vanderbilt mansion gets a new life on ultra-private Fisher Island

Highlights On Miami’s Fisher Island, the historic Vanderbilt Mansion, the hub of an exclusive club and community, has been extensively and painstakingly restored.

There are many Vanderbilt mansions, all of them grander, and certainly larger, than the relatively modest manse on Miami’s Fisher Island that bears the famous family name.

Ah, but if only you could see it — the beautifully proportioned stone and stucco Mediterranean Revival exterior, the octagonal entry, the soaring living room and the old dining room paneled in antique oak and mahogany, all of it extensively and exquisitely restored — then you might want to stay a while.

Alas, the 1930s estate, a designated Miami-Dade County historic landmark, sits at the heart of an ultra-private club and hotel on an island off the tip of Miami Beach that’s accessible only by ferry.

Or by a very large bank account.

In spite of the plush setting, though, the mansion had received little more than cosmetic care since the island was turned into a club and resort community some 25 years ago. The home, which has long served as the club’s hub, had come to be plagued by leaks, wood rot, structural issues and unkind adaptations.

The Fisher Island Club last year embarked on a full restoration, the culmination of a $60 million program of upgrades to the grounds and facilities. The work, now nearly complete, has brought the house back to the relaxed elegance of the few short years in which it served as the winter retreat for William K. Vanderbilt II, great-grandson of Cornelius, the railroad baron and begetter of one of the great American family fortunes.

“There were quite a few structural issues that were not readily apparent in a building that otherwise looked glamorous,’’ said renovation architect Richard Heisenbottle, whose team crawled under the house, opened up walls, removed and replaced ceilings and the roof to inspect and repair the mansion. “The good news is, it’s really in top-notch condition now. It really harkens back to the time of Vanderbilt.’’

The care lavished on the restoration extended to saving and refinishing, rather than replacing, the bronze-framed windows, the window hardware, and, whenever possible, even the original window glass, Heisenbottle said.

At a time when numerous waterfront Miami Beach homes from that same period are being demolished and replaced by mega-mansions, Heisenbottle says, the Vanderbilt restoration demonstrates how architectural landmarks from a bygone era can very much be adapted to the expectations — always eminently reasonable, one presumes — of today’s Bentley set, while keeping what made them worth saving in the first place.

Miami Beach, in fact, recently approved the demolition of a North Bay Road home by the Vanderbilt mansion’s original designer, Maurice Fatio, a Palm Beach architect still regarded as among the best ever to put pencil to a house plan in South Florida. The Swiss-born Fatio also designed Palm Beach-area homes for William Vanderbilt’s brother Harold and sister Consuelo.

Since Fatio designed it in 1935, the Fisher Island house had been added on to, including a ballroom and kitchen and a restaurant and lounge. But Heisenbottle said the additions were done sensitively and kept the focus where it belongs — on the original two-story, L-shaped house, which faces the Atlantic.

Though certainly opulent — the dining room and Vanderbilt’s second-floor study, for instance, are lined in antique paneling he brought from Europe, and its rooms boast marble fireplaces — the house was never meant to be Vizcaya. It had just two bedrooms, for Vanderbilt and his second wife, Rosamund. Her daughter, Rosemary, stayed in a spacious “cottage’’ the size of a small house, with an ornate stone doorway, that flanks the mansion. Another cottage served as Rosamund’s painting studio.

“This was really a getaway bungalow,’’ said Virginia Hanley, assistant project coordinator for the club’s renovation master plan. “Vanderbilt loved coming down here.’’

Commodore Cornelius Vanderbilt and his many descendants were prolific builders of extravagant Gilded Age mansions, all designed by the best architects of the age. Cornelius’ Manhattan home, the largest ever built in New York City, was demolished, but many others survive, some as publicly accessible attractions, including the famed Biltmore Estate in Asheville, N.C., the largest home in the United States, and the “Hyde Park’’ home in Hyde Park, N.Y.

Willie K., as he was known, was a dashing sailor and yachtsman who had navigated all over the world by a young age and launched the first organized auto races in the United States. The Long Island Parkway he built for racing became a toll road and helped pave the way for suburban development there.

His summer home, a 24-room mansion on a 43-acre estate on Long Island, N.Y., was designed by the architects of Manhattan’s Grand Central Station, built to serve the Vanderbilt rail empire. It, too, is a public museum.

GRAND SWAP

In the 1920s Vanderbilt, who frequented Palm Beach and Miami on his yacht, met Carl Fisher, the colorful, hucksterish developer of Miami Beach who had started the Indianapolis 500 auto race and the South Dixie Highway. He also owned Fisher Island, created when dredging of Government Cut split off the Miami Beach peninsula’s tip. The two agreed to a swap: seven acres of the island for Vanderbilt’s yacht.

At first, the Vanderbilts stayed on another yacht Willie K. owned when they visited the island, where little had been built, Hanley said. It’s unclear precisely when the $1.5 million estate was constructed, but Fatio began his plans in 1935 and county records suggest it was done by 1940.

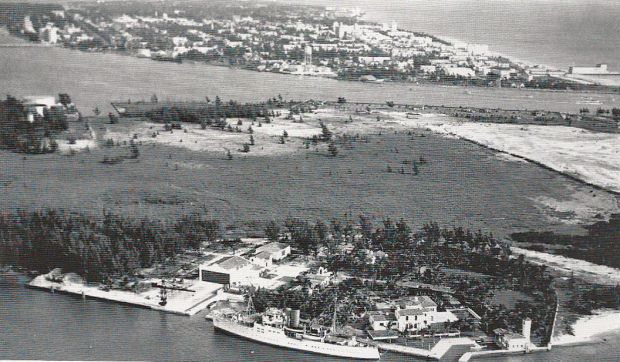

Vanderbilt named the estate Alva Base after the yacht, which bore his mother’s name. The estate also boasted a vast hangar for Vanderbilt’s seaplane and quarters for his household staff, which would come to Miami by train.

A celebrity in New York, where he had a townhouse on Fifth Avenue, Vanderbilt looked to Long Island and Fisher Island for peace and quiet, said Stephanie Gress, curator at the Vanderbilt museum.

“They built these to get away from everyone,’’ Gress said. “They had only very intimate gatherings.’’

But Vanderbilt was not able to enjoy Alva Base for long. He died in 1944, and his widow sold it to a U.S. Steel heir the following year.

Still, Vanderbilt, who gave $100,000 every year to the Miami Red Cross, had endeared himself to the locals, a county historic document says. In its obituary, The Miami Herald called him one of the city’s “most democratic residents and boosters.’’

The estate then passed through several well known owners closely linked to Miami’s history, including speedboat racer and inventor Gar Wood, who occupied it for 25 years, and Charles “Bebe’’ Rebozo, who used it as a playground for his friends — reportedly including his best pal, Richard Nixon — before deciding to develop it as a resort community.

The historic estate is now at the center of a 200-acre island community that encompasses more than 700 villa-like condos, a handful of free-standing homes, a nine-hole golf course, 18 tennis courts, two deep-water marinas, a beach, its own post office and firehouse, an astronomical observatory and a spa, housed in the former seaplane hangar. Not to mention several restaurants, an upscale food and wine market and a day school that teaches Mandarin to island residents’ kids.

But Fisher Island’s reputation had taken a bit of a hit over the past few years amid disagreements over control between club members and developers. Most facilities, including the mansion, had not received an upgrade since 1987. Last year The New York Times published a peculiar, much-circulated travel piece in which the author equally shellacked the quality of service in the hotel and the behavior of her own daughter.

While calling the Times piece unfair, the club’s leadership, in control of most of the island since reaching an agreement with the developers in 2006, brought in a new CEO to revamp the operation and guide the master plan for the mansion’s restoration and other improvements, which had been launched in 2007, to a conclusion.

‘QUITE A CHANGE’

“It’s quite a change. We intend with the renovation to make a statement. We are completely rejuvenated, refreshed,’’ said the new CEO, Bernard Lackner, who scaled back the hotel to a 15-room boutique operation to keep quality high. The guest cottages and servants’ quarters, also recently restored, are part of the hotel.

At the Vanderbilt house, the project meant extending the pool deck, reopening spaces in an entry loggia that had been blocked off years ago to create office space, refinishing millwork and wrought iron and, perhaps most dramatically, completely refurbishing the second story, which long served as a club within a club, open only to equity members. Once a dark, closed-in space, the expansive “snooker room,’’ formerly Rosamund’s bedroom, is now a bright, cozy lounge.

The only surviving piece of the Vanderbilts’ furniture, Rosamund’s vanity, sits in the room.

But Heisenbottle says the restored mansion is the crown jewel that sets the Fisher Island apart.

“It is unique, especially for Miami,’’ he said. “The Vanderbilts’ time here was limited, but he left a tremendous impact on Fisher Island.”

On September 5, 1927, Willie K. married Rosamund Lancaster Warburton, whose previous husband was related to merchant tycoon John Wanamaker. They traveled around the world in their new luxurious 265-foot Alva yacht, named for his mother.

In 1934, the Vanderbilts purchased a Sikorsky S-43 amphibian airplane that they to fly back and forth to Alva Base. By 1940, the Alva Base included the mansion, a seaplane hangar, a mooring dock for the Alva and an 11-hole golf course,

In this 1934 newsreel, William K. Vanderbilt Jr watched the arrival of his new seaplane to Alva Base.

Current Views: Alva Base, Fisher Island

Comments

Very nice site; I enjoyed your presentations.

As a side note, I am retired from Allison Transmission of Indianapolis, Indiana. The founder of Allison Transmission was James A. Allison, which had an island named after him called “Allison Island” in your area of Miami Beach. Jim Allison and Carl Fisher were co-partners in the founding of the Indianapolis 500 Motor Speedway; and as friends, bought property in the Miami Beach area. On this island Jim Allison built a mansion, hospital and an aquarium; which have by now been torn down or repurposed I’m sure. I believe Carl Fisher was also into real estate in the area.

As a modest request, as a retired historian for Allison Transmissions, I would greatly appreciate any historical information, pictures, etc. that you may have access to for the benefit of James A. Allison as it relates to his stay in Miami.

Thank you in advance. Neil Rude

Historian, Rolls-Royce Allison Division Indianapolis

6626 Ladoga Road

North Salem, Indian 46165

email .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)