Walter C. White- Driver of the Only Non-Gasoline Powered Racer in the Vanderbilt Cup Races

One of the most unique racers in the Vanderbilt Cup Races was the White Steamer. Built by a sewing machine and driven by Walter C. White, the son of the company's founder, the White Steamer competed in the 1905 American Elimination Trial and the 1905 Vanderbilt Cup Race.

Below is a profile of Walter C. White by Jim Donnelly which appeared in the June 2010 issue of Hemmings Classic Car, supplemented by my favorite White Steamer images.

Enjoy,

Howard Kroplick

Feature Article from Hemmings Classic Car

June, 2010 - Jim Donnelly

All in threes: brothers, life-altering products, and hugely successful businesses with worldwide impact. We are focusing here on Walter C. White, arguably the most influential of the three White brothers, who, as a group, represent the second generation of a family that founded a sizable segment of the American industrial revolution.

The story's foundation was laid in 1838, when Thomas H. White was born in Phillipston, Massachusetts. His own father had operated a chair factory, where he learned basic tool skills. He grew to adulthood as New England grew into the textile hub of the United States, and created a simple hand-operated sewing machine, which buyers raced to purchase as the demand for clothing boomed during the Civil War. Just after the war, White relocated his business and family to Cleveland, where many of his suppliers were now based.

Walter C. White, born in 1876 in Cleveland, was the last of three sons sired by Thomas H. White who would become powerful figures in the future automobile industry. By the time Walter was born, the White Sewing Machine Company was second only to Singer as the world's biggest. The company expanded further, to include products ranging from roller skates to kerosene lamps, the last adaptable to both wagons and horseless carriages. Walter, along with two of his brothers, Rollin and Windsor, was energized about automobiles very early on.

Thomas, who died in 1914, was content to let his sons expand into building cars. Rollin was hugely responsible for the formation of a White motor-car subsidiary in 1900 by inventing a workable flash boiler that allowed a steam-powered car to be quickly set into motion. Windsor focused on the new company's administration and finance; Walter was appointed as the company's president and chief executive officer. White steam car production jumped from four units in 1900 to 193 the following year, and to more than 1,000 in 1905, the enterprise's growth aided by the early addition of a condenser to help rapidly recycle exhaust steam.

In terms of its passenger cars, White has two enduring distinctions: As the auto industry's second-ranked producer of steam automobiles (behind only Stanley), and for the impeccably attentive and careful construction that made Whites internationally acclaimed. A White-designed racing car briefly held the world land-speed record in the flying mile. Thanks in large part to Walter's ministrations, White steamers attained White House peerage when one became the first motor vehicle used in an inaugural parade. The following year, Teddy Roosevelt grabbed the tiller of a White in Puerto Rico, the first U.S. president to drive an automobile. In 1909, the White Motor Corporation was formed as a freestanding manufacturer. At that point, the automobiles were made specifically under the White nameplate with no references to sewing machines.

Rollin White left the family business in 1914 to build farm tractors in Cleveland; his firm later became an Oliver holding. Before that happened, however, Walter White authorized a massively far-reaching product change, White's expansion into gasoline-powered vehicles. While only a few fingers' full of them survive today, gas-burning cars instantly accounted for half of White's overall automotive production. That's the main reason that White survived as a company and Stanley didn't.

The final White steam car was assembled in 1911, and a year later, White introduced a premium, robust line of six-cylinder cars producing 60hp, all with shaft drive and four-speed transmissions. By this time, White was also moving into the world of trucks, which it had dabbled with since the early steam days. Walter White is credited today with turning White into an enduring force in truck manufacturing. White's huge straight-six cars were way too expensive for big volume, but their engines started reaching under White truck hoods with dispatch.

One such rig went to the Army Corps of Engineers and was successfully driven across Alaska. Walter White took the family business exclusively into truck production beginning in 1916, reorganizing it again as the White Motor Company. He also convinced the Army to buy Whites during World War I. Although its contemporary, the Mack Bulldog, was the truck that passed into American folklore, these early White one- and three-ton trucks were the ones adopted as standard Army designs, with the War Department buying about 18,000 of them in all. Their success under fire bred more business, including White's score in motorizing San Francisco city transit just after the war ended. White rang up more highly visible sales by designing and building the first sightseeing buses used in Yellowstone National Park.

As with other producers, White devoted engineering resources to designing heavier, higher-capacity trucks as an intercity road network emerged during the 1920s. A five-ton design was a sales leader for much of the decade, and in 1928, White introduced the Model 58, a 10-ton truck whose rollout coincided with relaxed weight restrictions. Although White suffered badly during the Depression, recovering following a brief merger with Studebaker, Walter White wasn't around to see it. He died in a traffic accident on September 29, 1929.

Walter C. White (third from the left) and his White racing team in front of their headquarters at Aloysius Huwer’s Bulls Head Hotel. A popular location for viewing the races in 1905 and 1906, the hotel and garage barn were located at the junction of North Hempstead Turnpike and Glen Cove Road in Greenvale.

White can be seen here driving the 40-HP White Steamer into the Bulls Head Auto & Wagon Shed.

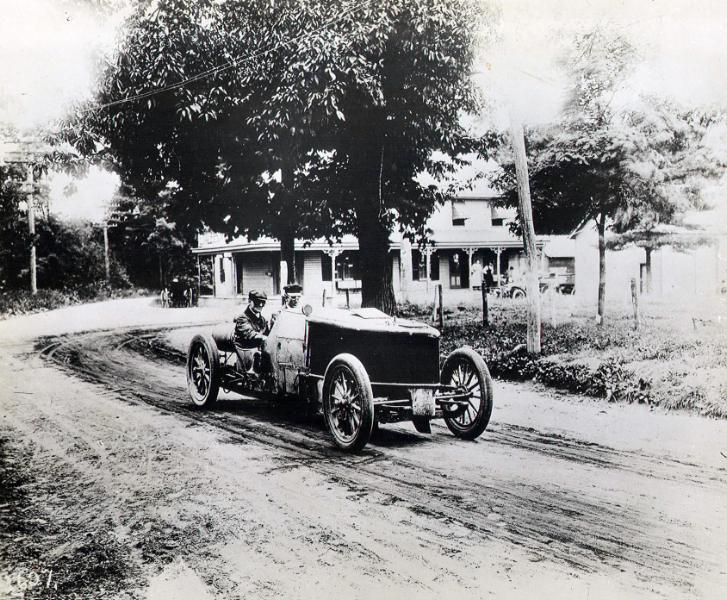

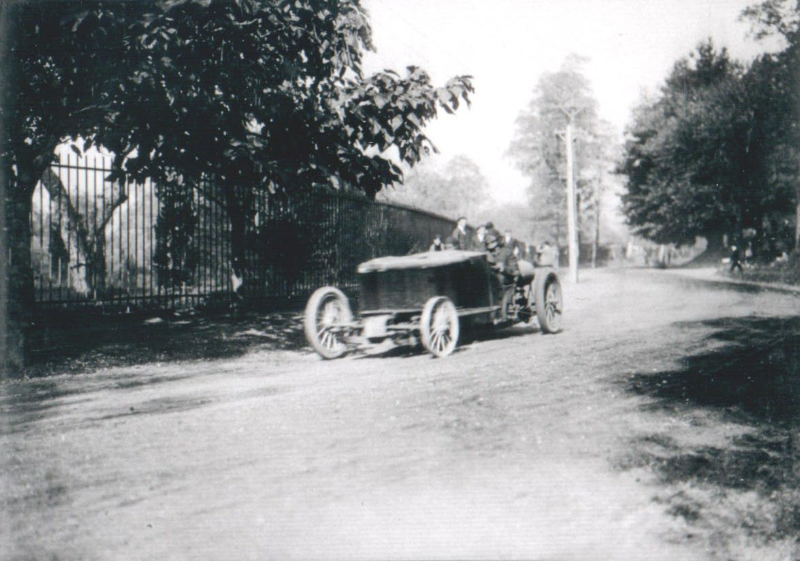

White doing a practice run on Glen Cove Road in front of his headquarters.

The White Steamer in front of Clarence Mackay's Harbor Hill estate off Glen Cove Road in Roslyn (now East Hills).

1905 American Elimination Trial

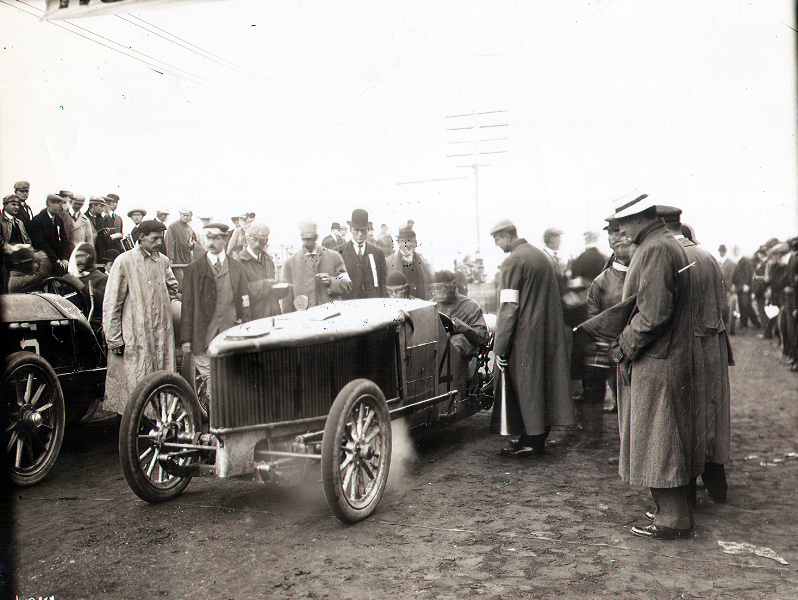

On September 23, 1905, the American Elimination Trial was held to determine the five entries from 12 American candidates. A four-lap race totaling 113.2 miles was to be held over the new 1905 course. Walter White had wrecked the car in a practice run just the previous day, slamming into a telephone pole. The team had scrambled to ready the car for the race as it required extensive repairs. Can you find referee William K. Vanderbilt , Jr.?

Although finishing seventh, the Vanderbilt Cup Race Commission selected the White Steamer to be one of the five American entries.

1905 Vanderbilt Cup Race

The #19 White Steamer at the starting line.

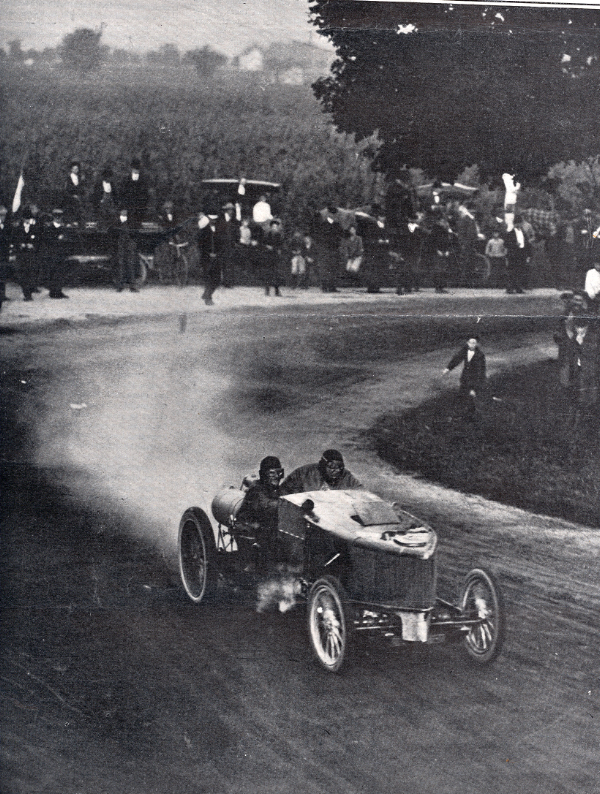

On Jericho Turnpike near the Mineola grandstands.

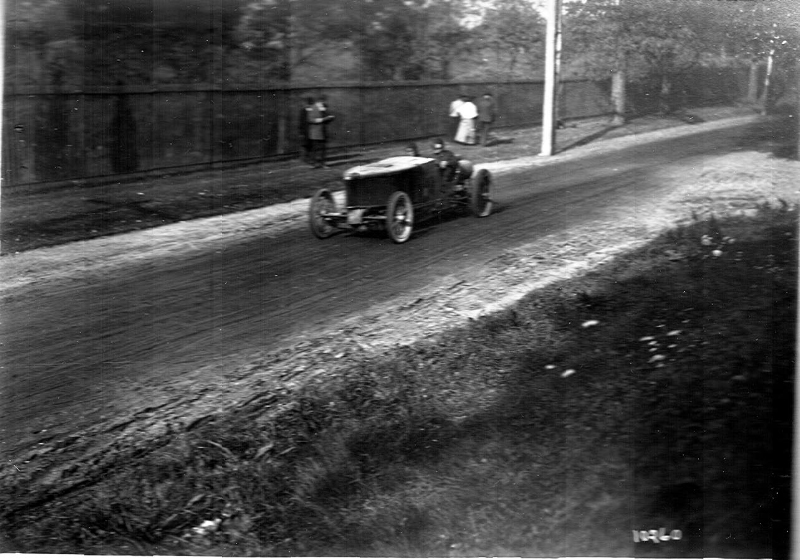

The steamer sputtered early in the race. During lap five, the steamer punctured its left front tire at the Guinea Woods Turn and limped on its rim as it passed William K. Vanderbilt Jr.’s Deepdale estate in Lake Success.

Check out the rim on the front left wheel and the gates of the Deppdale estate.

Portions of the gates surrounding the Deepdale estate are still standing today on Lakeville Avenue.

Comments